The coming of the railways from the 1840s changed the shape of long distance travel; stage coaches and wagons were slow and cumbersome. However, in the West Riding, the close proximity of the prosperous commercial centres meant that road transport continued to be a viable option for goods – the double handling necessitated by rail journeys made those less economic: the goods had to be taken by wagon to the rail head,unloaded onto the train, shipped, then unloaded off the train onto a wagon for delivery. Haulage businesses and carriers such as the Hansons of Milnsbridge thrived. Rail passengers also required road transport to take them to the train station, either personal or public; the major London termini are all situated in built up locations and the congestion around them was notorious.

For those who did not keep at least a pony and trap or a riding horse, local public transport was provided by four‐wheeled hackney coaches and later by two‐wheeled cabs (from ʹcabrioletʹ – with a folding hood) drawn by a single horse. The lighter four‐wheeled ʹgrowlerʹ was introduced shortly after the Hansom cab (completely remodelled by John Chapman) came into use in the mid 1830s. By 1840, there were around a dozen hackneymen in Leeds, for example; one John Germaine operated cabs, hackney coaches and omnibuses as well as running a beerhouse. The growlers were used for heavier work, transporting station luggage and as coachbuilder G N Hooper wrote in the 1880s, ʹTommy Atkins and his friends from Aldershot or Mary Jane and her boxes to her new place in a distant suburbʹ (1).

Initially the trade was unregulated; indoor servants were obliged to leave their employment on marriage and one of the Metropolitan Commissioners commented ʹa gentlemanʹs servant saves up two or £300 and fancies he can do better with a coach than any other man: the workhouses are filled with hackney coachmenʹs wives and children at this momentʹ (2).

By 1880, Manchester had 100 hansoms and 361 four‐wheelers; in May 1868, the Minutes of the Huddersfield Hackney Coach and Lodging House Committee record that the Committee had made the annual inspection of Hackney Carriages and had granted 30 renewed licences. In May 1890, the Huddersfield Watch Hackney Coach Sub‐Committee and Chief Constable carried out the annual inspection, now covering 48 Cabs, 33 Hansoms, 42 Waggonettes and one Omnibus, finding that generally the 121 vehicles ʹwere in satisfactory condition with a few exceptionsʹ (3). In 1891, the Committee observed that ʹIt is against the practice (rules) of the Committee to grant licences for wagonettes to persons resident outside the borough (Meltham and Linthwaite)ʹ.

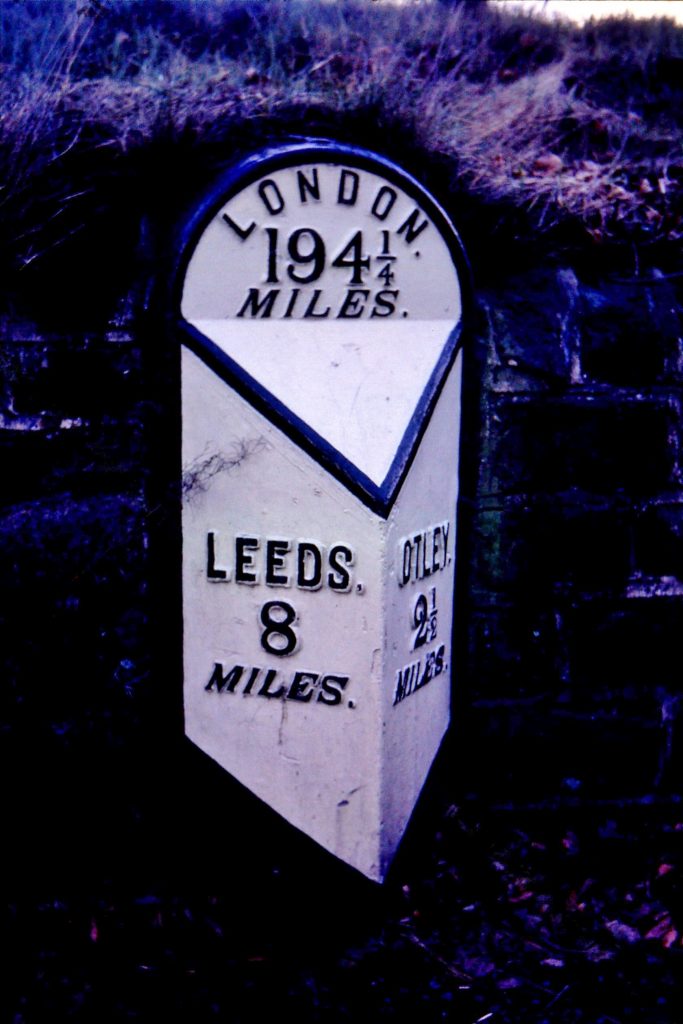

The cab fares were measured from the Market Cross, although in March 1890 the Fartown, Deighton and Bradley Sub‐Committee proposed that cab distances should be measured from the station instead of the Market Cross. The same Sub Committee had reported ʹthe necessity of revising the table of distances in connection with the hire of cabs in the Borough, more especially with reference to the Fartown Districtʹ. The Committee resolved that ʹthe Borough Surveyor should revise the cab distances for the whole Boroughʹ and this was duly carried out, as reflected in the little red pocket Borough of Huddersfield Year Book. The Cab Fares page showed charges were levelled on distances for a minimum 1 mile and for every succeeding half mile (or by quarter hours).

Huddersfield is unique in having triangular stone markers at half mile intervals on the roads within the borough, stating the distances to and from the Market Cross – these were the cab fare stages, although in the 1890 Year Book, all the datum points mentioned are chapels, toll bars, houses or junctions which suggests that the ʹTo & Fromʹ stones were not in situ in 1890. On the Bradford Road, the fare stage at ʹa mark on the wall 11 yards N of Mr Dewhirstʹs entrance gatesʹ was reviewed by the Borough Surveyor and moved a few yards northwards, against the shoeing forge (on the corner of modern Ashbrow Road – the bus fare stage is still known as The Smithy today); the distance from the Market Cross was 1½ miles and the fare was 1s 3d for a two‐wheeled cab, 1/6 for a four wheeler. The furthest distance recorded in the Year Book was to Thongsbridge Toll Bar, 5 miles 396 yards; no fare was specified.

Around the same time, there was a request for additional cabs on the stands at the railway station; such work was often ʹprivilegedʹ ie the cabmen paid a fee to the station. By 1894, the Light and Watch Committee was considering the Regulation of Traffic by the Railway Station; it was resolved that ʹarc electric lights should replace the two gas lamps by the Peel statueʹ and that horses were to face east.

A glance at the census returns for 1871 and 1881 reveals that many men were employed as coachmen or cab drivers with the occasional teamer; someone has pencilled ʹgroomʹ alongside many of these entries, perhaps an attempt at a generic enumeration. However, there is no indication whether the coachmen were in domestic, commercial or public service. Ostlers (also ʹgroomsʹ) would have been required at all the inns, theatres and other meeting places to take care of visitorsʹ horses or stagecoach horses.

One local family that became closely connected with the coaching, cab and livery trades in the 1880s was the Darwins. Thomas Darwin was born in Holmfirth in 1853, one of the six sons of James, a weaver who moved to Huddersfield around 1855 and was working as a Woollen Sorter. Most of the Fartown neighbours were employed in the woollen trades, including Thomasʹ older brother George H, although brother Frederick was a ʹlabourer on roadsʹ. Aged 18 at 1871 census, Thomas was employed as a butcher, living with his parents in Bradford Road. By 1881, Thomas was listed as a Master Butcher, living with the Bowtrey family at 121 Halifax Old Road; in October that year he married Elizabeth Ann Roberts of South Crosland at the Parish Church, Holmfirth.

With the granting of the operational licence in 1882, Huddersfield became the first municipality in Great Britain to construct and operate their own tramway system – such systems as existed elsewhere were privately run.

The first ten miles of Huddersfield Tramways track were laid down in 1882 and a steam engine drawing a car was given the first trial run on Chapel Hill in November that year; it was planned that the Paddock route would be operated by cable but this was abandoned. The first regular service was between the Red Lion Hotel, Lockwood and the Royal Hotel at Fartown (Toll) Bar, commencing in January 1883. In the first year of operation, the Corporation had six steam locomotives and the revenue was £1,277.

The fare from Lockwood to Fartown Bar was 2d inside, 1d on the top deck; the inside fare to the interim fare stage at Hebble Bridge (near the junction of Hillhouse Road with Bradford Road) was 1d. However, it was deemed too dangerous to operate steam trams in King Street, so from 1885 – 1888, the Moldgreen trams were pulled by horse traction (4). Similar consideration must have been given to the Fartown section because in the Huddersfield Town Council Minutes of 22 August 1885, the sub‐committee had decided that the Fartown Tram was to be run with horses; although they would undertake to confer with Mr Longbottom about his proposal in future, they accepted the tender of Mr Thomas Darwin of Fartown to work the route with horses. It was further decided that as soon as practicable the cars should be every quarter of an hour on that route.

That this actually operated is corroborated by a letter in an undated newspaper cutting (5) from Mr James H Earnshaw of 18 Springwood Street, stating ʹThe first horse tram to run in Huddersfield began to run to Moldgreen from September 1885 to March 1888. A few months after, two horse trams were run on the Fartown section, horsed by Mr Thomas Darwin and continued to November 1886. I was the tram driver on the Fartown section for the last three months of their running and William Cromack was the other driverʹ.

By 1897, the Corporation had a rolling stock of 26 steam locomotives and 26 double deck bogey cars; the revenue was £30,193. Conversion to an electric track system was begun in 1899 and completed in 1902.

Was it marriage that caused the young entrepreneur to branch out from butchery? Slaterʹs 1887 Huddersfield Directory lists him as a coach proprietor and cab owner, working from 158 Bradford Road North, the Miners Arms Beerhouse (now the Railway Inn) near Fartown Bar, then run by his mother Ann. Two dozen cab owners are listed, including older brother George H, who is also a postmaster at 27 Wasps Nest Road, and William Cromack.

By the 1891 edition of Slaterʹs, Thomas is building a successful business as a Livery Stable Keeper and coach/cab proprietor; his brothers are in associated roles, George H is a jobmaster (hiring out livery) as well as a postmaster, Frederick is a cab driver (though the census listed him as a Corporation yardman), John is a cab driver in Cross Grove Street, William is a teamer (a driver of a team of horses used for hauling) at 18A Upper Aspley and Thomas F (son of George H) is a cab driver living at Norman Road, Birkby.

Thomasʹ livery stables continue to prosper, in extensive premises on Flint Street called Fartown Mews, proudly engraved on his letterhead. He is often mentioned in the Chronicle, including for winning a four‐wheel competition or taking groups of ladies or children on pleasant outings – the children taken to Sunny Vale Gardens in 1893 were each presented with five tickets including for the boats, swings and automata. In the same year, the Chronicle notes, he provided stabling for the June Exhibition, the Grandest Programme of the Season: ʹAll the horses for this Night will be specially selected from the most WILD AND VICIOUS HORSES in this vicinity.ʹ

In 1894, he treated the yard stablemen and coachbuilders in his employ to a capital dinner at the Miners Arms, then run by his (less reputable) brother James. Note the reference to ʹcoachbuildersʹ rather than ʹcoachmenʹ so presumably he had an in‐house maintenance team.

Around this time, another revolution in transport was noisily beginning. The Germans (Daimler and Benz) had been producing motor cars since the 1880s although the French dominated the production of cars in Europe until 1933, when Britain took over (6). British‐built Daimlers (under licence) began in 1896, the same year that the Locomotives on Highways Act removed the strict rules on UK speed limits. The RAC was founded in 1897 and the Yorkshire Automobile Club in 1900, one of the strongest in the provinces by 1905, with 600 members (7).

The Rippon Brothers of Viaduct Street were coachbuilders; they did not actually claim descent from the eponymous coach builder to Elizabeth 1st, nor did they deny it. However, they did adhere to the very highest standards and they began coachbuilding bodies on various Continental automobile chassis, including Spyker; in 1906 they began a partnership with Rolls Royce, building bespoke bodywork to customersʹ orders. The early horseless carriages often resembled their antecedents, with the driver exposed at the front, as the coachman had been on the box.

Tram in Viaduct Street by Rippon Bros (kirkleesimages.org.uk)

Tram in Viaduct Street by Rippon Bros (kirkleesimages.org.uk)

The early adopters were often wealthy young men with an engineering bent, essential because the vehicles were most unreliable, needing repairs by the roadside and frequent changes of tyres or wheels as a result of punctures. However, as the vehicles became more reliable in the early 1900s and tyre technology improved, they were bought by private families to supplement the carriage. The driving skills required were not those of the horseman, more of the ʹstokerʹ, some vehicles being propelled by steam, hence the term ʹChauffeurʹ. The wealthy often imported a French or German driver with their cars. Older coachmen found it difficult to adapt and ʹHome, Jamesʹ by Lord Montagu of Beaulieu contains some amusing and insightful anecdotes. A young groom or male house‐servant might be delegated to learn how to operate and maintain the thing; there was no standard layout of the controls. A provider such as Rippons might give elementary instruction but after that, they were on their own, or at the mercy of one of the repair ʹgaragesʹ that sprang up, providing servicing as well as storage. Domestic accommodations for cars were known as ʹcar housesʹ (8).

The career of the live‐in young coachman employed in his declining years by Henry Dewhurst at Fartown Lodge provides an example. The 1901 census lists 26 year old Arthur Cockayne, who hailed from Swanwick, Belper, on the Derbyshire/Nottinghamshire borders. Live‐in domestic staff were not permitted to be married, but this did not apply to outdoor staff such as coachmen, for whom separate accommodation could be provided. Recruitment was either by recommendation or through advertisements in magazines or newspapers, both local and national; by the 1890s, most large towns had one or more servant registries (9) ‐ the Huddersfield Chronicle carried advertisements by the Lincoln Registry at Springwood Street, for ʹServants for Town and Countryʹ.

Servants frequently travelled long distances for work – employers often preferred staff with no local connections and therefore less likelihood of gossip in the neighbourhood.

After Henry Dewhurst died ʹof senile decayʹ in 1902, Arthur Cockayne married Margaret Allen from Durham at Huddersfield in December 1904 and went on to take advantage of that new development, the automobile. He moved to Middleton in Leeds where his daughter Beatrice Rosetta was born, then to York; by the 1911 census, aged 35, he was employed as a chauffeur, living in Walton Road, Wetherby. The chauffeur was a professional, falling outside the customary servant hierarchy, as had the governess; he was often in close contact with the mistress of the house and scandalous indiscretions occasionally resulted.

Little formal instruction was available and driving licences were not implemented until 1910. In that year, doctorʹs son Stanley Roberts realised that motoring was going to be big business and set up his own driving school, naming it The British School of Motoring, now known simply as BSM. Previously an engineerʹs apprentice with Thomas Sopwith, Roberts was a motoring fanatic and persuaded his parents to rent out their garage at 65 Peckham Rye to his fledgling business and to house his prized possession, a Dutch‐built Spyker. Offering a ʹPopular Course of Mechanism and Drivingʹ, Robertsʹ first pupil was a former coachman, whom he trained to become a chauffeur; the business expanded nationwide.

Thomas Darwin also kept abreast of the new developments in the twentieth century as owner‐drivers enthusiastically embraced the automobile, catering for both those who drove and those who did not. He is generally listed as a cab proprietor in the trades directories, but also as a funeral director; his 1906 letter‐head notes that he offers the ʹNew Silent Tyred Funeral Carsʹ. The history of hauliers Joseph Hanson & Sons of Milnsbridge records that ʹIn 1920, Thomas Darwens, wedding and funeral car hire, was acquired. Some 8 years later the old cars were replaced with Rolls Royces and the limousine service continued for 50 years.ʹ Thomas became a major shareholder in the Yorkshire Motor Car Co, of Elland Road, Brighouse, calling in his debenture in 1922 and later was appointed a receiver for the business.

His own operations were now managed by his nephews James Henry Heaton Darwin and Norman Darwin, sons of George H, the jobmaster and postmaster; Norman ran the site at Flint Street trading as Fartown Garage, also funeral directors, supplying motor hearses, landaulettes, horse carriages &c, while James H H, his family and his younger brother John Edward were operating out of Fartown Lodge Mews, the former home of Arthur Cockayne the coachman, described as Fartown Lodge Garage in the Halifax & Huddersfield District Trades Directory (10).

Thomasʹ draft will in 1926 bequeathed ʹall stock in trade, horses, carriages, harness and other effects … as a Carriage Proprietorʹ to his nephew James H H, and ʹthe motor hearse and cars as a Garage Proprietor in Flint Streetʹ to his nephew Norman. Thomas died in 1938, the year that Norman is listed as a Director of the newly incorporated Silver Wheels (Hire) Ltd. James H H had an ironic end at the age of 57; in 1930 his daughter wrote to Thomas in great distress from Vancouver, reporting that he had been knocked down by a car and killed (11).

The Darwinsʹ connection with the coachmanʹs house continued until the 1950s; in the early 1930s, it was bought by another cab proprietor, Walter Vosper Holder Halstead, whose sister Beatrice then married James HHʹs son Stanley; they all lived together in the coachmanʹs house and continued to run old‐fashioned cars as taxis, perhaps those sold off by Hansons. After Walterʹs death in 1953, Beatrice and Stanley moved out, and the property was bought by another member of the motor trade, Olaf Olsen the Volvo dealer. He had completed his coachwork apprenticeship at Rippon Bros and apparently had painted the coachlines on two of the Rolls Royces supplied to Beaulieu, presumably to be driven by Lord Montagueʹs chauffeurs, although the Volvo was fast gaining a reputation for outstanding reliability, too!

Jan Scrine, © The Milestone Society, 2020

References

1,2 Trevor May: Victorian and Edwardian Horse Cabs; Shire Publications, Oxford, 2009

3 Huddersfield Corporation Light and Watch Committee Minutes, May 1890

4 The Huddersfield Examiner, 26/7/1952, 70th Anniversary Supplement

5 Huddersfield Local History Reference Library, ʹTramsʹ file

6,8 Kathryn A Morrison and John Minnis: Carscapes: the Motor Car, Architecture and Landscape in England; English Heritage, 2012

7 Motoring Annual 1907, quoted in Jonathan Wood: Rippon Brothers, a Coachbuilder of Renown; 2012

9 Trevor May: The Victorian Domestic Servant; Shire Publications, Oxford, 2009

10 Halifax & Huddersfield District Trades Directory 1925 – 1926, p 121

11 West Yorkshire Archives, Darwin files.

This article was originally published in MILESTONES & WAYMARKERS, 2020, vol 12.

Tram in Viaduct Street by Rippon Bros (kirkleesimages.org.uk)

Tram in Viaduct Street by Rippon Bros (kirkleesimages.org.uk)